Experts on Next Pandemic: Could Arrive Anytime, Could Be From Animals

The next pandemic could arrive at any moment and could come from animals; experts warn as countries continue its fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

The next pandemic could be prevented by ramping up governments' pandemic prevention efforts, according to experts.

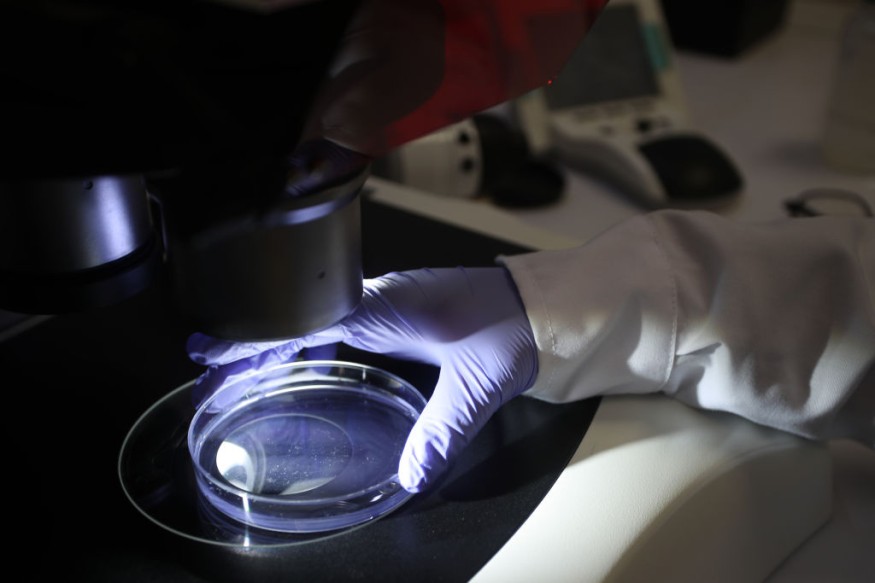

These efforts include deploying teams of biologists, zoologists, and veterinarians to start monitoring animals and the people who interact with them.

Experts say there should be an army of medical and scientific experts ready to stamp out the next deadly virus before an animal disease evolves into a global pandemic.

The World Health Organization said that around one billion cases and millions of deaths each year could be traced back to animal populations' disease.

Researchers have seen more than 30 bacteria or viruses that can infect humans.

More than three-quarters of those are believed to have originated from animals.

Scientists also said that the next pandemic could be accelerating dramatically due to humans' proximity to wildlife.

Years ago, other diseases infected many, such as SARS, West Nile, Ebola, Zika, and now COVID-19.

Many of these pandemics came from bats species, which can be spread between people through coughing and sneezing or insects like mosquitoes.

Dr. Tracey McNamara, a pathology professor at Western University of Health Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine, said that the time between these viral outbreaks is getting shorter.

Dr. Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, said that we can only sustain an outbreak maybe once every decade.

Daszak added that the rate we are going is not sustainable.

The two scientific experts said the COVID-19 pandemic did not surprise them.

For years, the industry has been warning governments and the public that wild animals can threaten the human population with the viruses they carry.

McNamara was part of the "Red Dawn" group, a now-infamous email chain of top scientists.

The group had asked the U.S. government officials to increase domestic defense when COVID-19 was considered a problem in China.

Daszak also spent much of his career searching for the next pandemic-causing virus in bat caves in Asia.

Daszak's U.S. government funding for science was cut back in April.

PREDICT also shared the same fate when its funding quietly lapsed in 2019.

PREDICT was a U.S.-funded early-warning system, which was launched in 2009 as a response to the H5N1 bird flu outbreak.

Interaction with wildlife increases more as populations expand.

Cutting down forest pushes animals out of their own homes and come to human communities.

"We see the appearance of new diseases like COVID[-19] overwhelmingly coming from wild animals and to a lesser extent, domesticated animals. That reflects increasing contact between people and wildlife, in particular. And of course, the reality that we live in a highly connected world with many densely populated cities," Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a co-author of the study, was quoted in a report.

Bernstein pointed out that significantly reducing deforestation and wildlife trade would have other benefits, such as protecting global diversity.

"But there are other things that protecting forests does: It prevents fires. And so you see the compounding value that occurs when you protect forests. And now we add another dimension, which is the prevention of disease spread," he was quoted.

Check these out:

WHO Warns Countries Cannot Pretend COVID-19 Pandemic Is Over

WHO Announces the Novel Coronavirus as a Pandemic

Online Petition Calling for WHO Director-General's Resignation Nears 1 Million Signatures

Subscribe to Latin Post!

Sign up for our free newsletter for the Latest coverage!